The Premier League's Centre of Gravity Is Shifting Southwards

But don't write off the rest of the country's football clubs

On Saturday Nottingham Forest joined Fulham and Bournemouth in reaching the Premier League for the 2022/23 season.

These three clubs will replace relegated Burnley, Watford and Norwich City.

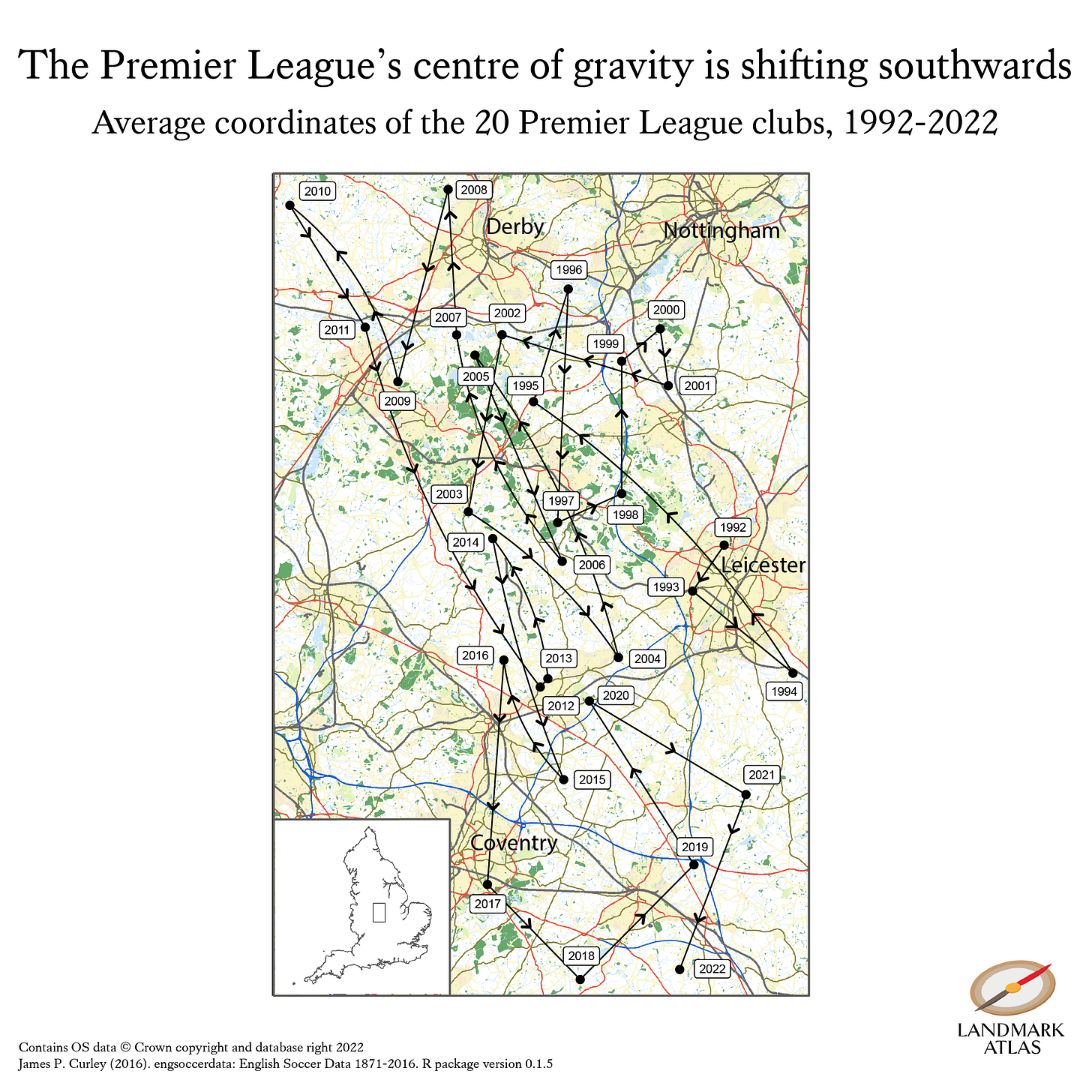

Now we know which 20 clubs will compete in England’s top division next season, we can see that the centre of gravity of the Premier League continues its southward shift.

This map takes the geographical coordinates of the stadiums of each club that competed in each season of the Premier League since its inception and plots their average central position, known as a centroid.

A more northerly centroid indicates that Premier League season was more dominated by clubs from northern England. A more southerly centroid shows that London and southern clubs were in the ascendancy that year.

The arrows on the map track the central point as it meanders around the Midlands from 1992 to 2022.

This is the story of that journey.

1992-97:

The centre of gravity starts around Leicester, although the Foxes didn’t make an appearance in the Premiership, as it was known then, until 1994/95.

Notably that 1994/95 season was the one most dominated by clubs towards the east of England.

A joint-record seven London clubs as well as Norwich City and Ipswich Town from East Anglia pulled the centre of gravity towards the east coast.

It took a sharp westward turn the following season however as Leicester, Norwich and Ipswich were all relegated that year.

In 1996/97 the centre moved to the north. Nine of the 20 clubs in the Premier League that season were from northern England with a further five from the Midlands. That was the furthest north the centre of gravity would travel until 2008/09.

2008-11: Lancashire in the ascendancy

The 2008/09 season featured a lot of trips to Lancashire.

Seven clubs from the historic county competed in the top flight that year: Manchester United, Liverpool, Everton, Manchester City, Wigan Athletic, Bolton Wanderers and Blackburn Rovers.

They were joined by Newcastle United, Sunderland and Middlesbrough from the North East (the last season to date these three rivals have been in the top flight together) and Hull City from Yorkshire.

Only five of those 11 clubs played in the Premier League last season. These five had contrasting fortunes: Manchester City and Liverpool divided up the domestic trophies between them while Manchester United fans looked on enviously. Newcastle United climbed steadily out of trouble while Everton came alarmingly close to terminating their 68 season streak in the English top flight.

2015-22: heading south

Journalists in 2016 and 2017 were starting to notice an apparent trend of London dominating the Premier League at the expense of the North.

The 2018/19 season was the most southern edition of the Premier League so far. There were six London clubs in the top flight that year, as well as three on England’s south coast (Bournemouth, Southampton and Brighton) plus Cardiff and Watford.

Next season will see seven clubs from England’s capital, including three within a few miles of each other in west London (Chelsea, Brentford and Fulham).

So does London’s social scene, transport links and warmer, dryer climate give its football clubs a decisive advantage in attracting better players over their northern rivals? Is England’s national game tilting towards the south permanently?

London to dominate the Premier League permanently?

Football, like politics or the economy, moves in cycles. English football generally is in a strong cycle at the moment. English sides’ recent strong performances in European competitions and the national team’s runs at the 2018 World Cup and Euro 2020 are good evidence of this.

This strong cycle follows a weak one from 2012 to 2017 during which English clubs reached the Champions League semi-finals on just three occasions. During this weak cycle Leicester managed to steal a march on the bigger clubs like Arsenal and secure an astonishing league title.

I think it’s likely that the current heavy representation of southern English clubs at the expense of northern ones is one of these cycles.

My view is that a club’s financial muscle, quality of management, both in the dugout and at board level, recent success and luck matter much more than its geographical location in predicting future performance.

Liverpool have an elite manager in Jurgen Klopp and have turned themselves a well-run club that regularly competes for the Premier League and the Champions League. This feeds a virtuous circle which means they have no trouble persuading foreign players to swap Portugal or Rome for Merseyside.

It’s possible to find other examples of stable, well-run clubs in the Midlands and the North (see also: Leicester, Burnley, Wolves and Manchester City). A southerly latitude hasn’t stopped the likes of Portsmouth, Charlton Athletic and Leyton Orient from slipping a long way down the football pyramid.

It could have been so different for Leyton Orient if they had won their penalty shootout against Rotherham in May 2014. They would have been promoted to the Championship and who knows, perhaps from there they could have made the jump like Brentford have to the Premier League. As it happened the club was sold to Italian businessman Francesco Becchetti in July of that year. Following the sale Orient entered a calamitous downward spiral that culminated in their relegation to the National League in 2017. In the season just gone they finished 13th in League Two. If luck deserts your club at the wrong time it can take years to undo the damage.

Some changes of ownership are more fortunate. In the VICE piece I linked to above it talked about the struggles of the North East clubs, linking it to the region’s post-industrial decline. It’s a seductive narrative but then along comes a consortium including Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund and one day Newcastle United become one of the richest clubs in the world. Who knows which club will suddenly come into billions of pounds of wealth next?

That’s not to say that London has no special attraction whatsoever. Its size, economy and transport links are far greater than any other city in Britain. But I’d be wary of ascribing too much importance to the capital factor, or to predict a permanent cluster of southern teams in England’s top flight. There are just too many other variables at play.

Caveats and acknowledgments

The centroids data uses the coordinates of teams’ current stadiums and not past ones (e.g. the Emirates Stadium for Arsenal rather than Highbury). Wimbledon FC uses the old Plough Lane rather than the new Plough Lane used by AFC Wimbledon.

The football data used for the different seasons comes from James Curley and his engsoccerdata package in R.