The Titanic Disaster Was Southampton's First Day on the Somme

Mapping the terrible impact of the sinking on the port city

If you ask a British person to name a tragic waste of life that occurred in the early years of the 20th century, they might well reply with the First Day on the Somme.

On 1 July 1916 the British Army lost 19,240 men in a large attack against the German lines during the First World War. Many thousands more were wounded.

The news began to filter through back to Britain in the following days. Cities, towns and villages up and down the country would have to comprehend the horror of what had happened.

But the city of Southampton had already been through this, four years earlier and 110 years ago, with the sinking of the Titanic.

Survival chances

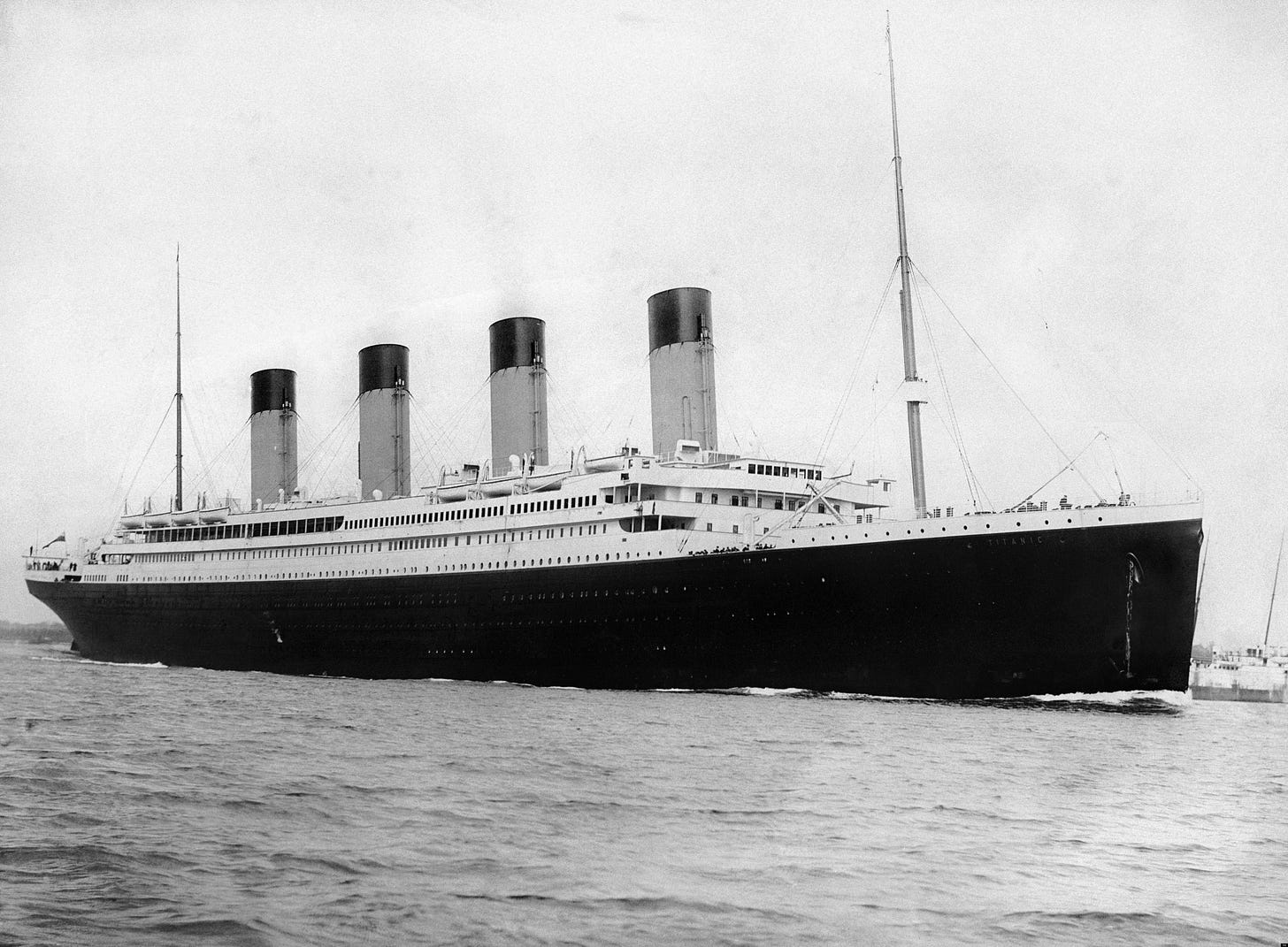

One reason why we have such an enduring fascination with the Titanic was that she was a microcosm of the British class system in operation at the time.

The passengers were segregated according to their class. First class passengers were treated to unrivalled luxury on the top decks of the ship. Third class passengers were accommodated in more basic, but still relatively comfortable, cabins in the lower desks. The crew also mostly spent their time off duty in the bowels of the ship.

To survive the disaster you needed to get into a lifeboat. First class accommodation was physically closer to the lifeboats, which meant these passengers were more likely to be able to get to safety first.

There was no public address system on Titanic, so instructions on what to do had to be relayed via word of mouth. This took longer to reach the lower decks.

Many of the lifeboats were launched far below full capacity, so by the time the third class passengers reached the top decks many of the boats had already been launched. In addition many of the crew heroically remained at their posts, depriving themselves of any chance of survival.

Two years later, the First World War would sweep much of this class system away for ever.

Southampton wakes up to disaster

The chart above shows that crew members had the lowest odds of survival of all the classes of people on board Titanic.

Approximately 709 crew members listed their address in Southampton.

I say ‘approximately’ because there has always been some confusion about who exactly was on board the ship on 14 April 1912. Some crew members may have given false information or clerks may have transcribed it incorrectly.

Approximately 528 crew members were lost from Southampton. They ranged from Sotonians born and bred to those who had been staying in hotels prior to the voyage.

My map below shows where those crew who were lost on board Titanic were from in Southampton:

More than 500 families lost a loved one from Titanic’s crew.

They lived all over the city as it was at the time. Many lived in the crowded streets close to the Port. Much of modern suburban city was farmland in 1912, which is why there aren’t many dots in the outer reaches of the city.

Some streets were particularly badly hit. Derby Road in Nicholstown lost six men. Five families in Russell Street near St Mary’s lost a loved one each.

The youngest crew member from Southampton to die was just 15 years old. Archie Barrett was a bell boy who lived at 164 Northumberland Road in Nicholstown.

This was the memorial message his parents put in the local newspaper for him:

..As we gaze at your picture that hangs on the wall, Your smile and your welcome we often recall. We miss you and mourn you in sorrow unseen. And dwell on the memory of days that have been.

The numbness that Archie’s parents must have experienced when the news came through in April 1912 would also have been felt by some of their neighbours.

Three other families on Northumberland Road lost family members aboard Titanic. Percy Ahier, a 20-year-old steward from Jersey; Ernest Abbott, a 21-year-old pantryman and Richard Moores, a 38-year-old greaser were all killed from that street.

This collective grief would be replicated up and down the country four years later in July 1916.

Caveats

There are some caveats for my map.

The addresses were automatically geocoded, which may or may not be completely accurate. Some are accurate to the street number, others are not.

Southampton’s street layout has substantially changed in the last 110 years. With the help of old maps and Sotonopedia I was able to piece together where many of the old streets ran. However this wasn’t completely accurate and I had to leave a few addresses out altogether because I couldn’t establish where they had been.

Acknowledgments

As well as the acknowledgments in the chart and map, I’d like to show appreciation for:

Southampton City Council for publishing the source data on crew members.

OpenStreetMap for map data, which is available under the Open Data Commons Open Data Licence.

National Library of Scotland for the old maps of Southampton.

Sotonopedia for details of old Southampton