I was intrigued to read last year about a Scottish village called Inverie.

The story told how the locals had bought their local pub, the Old Forge, with more than £320,000 of money raised from various sources.

It was a heart-warming tale about how a village came together to secure the future of one of its most important assets.

One detail caught my eye in particular:

The Old Forge is accessible only by ferry or via a two-day trek through the Knoydart peninsula on the west coast of Scotland.

Could that really be true? Could there really be a village in Scotland that is not connected to the country’s road network?

If I had known about Knoydart in 2021, I might have diverted our route along the North Coast 500 southwards slightly to check it out, as far as I could:

I decided to investigate.

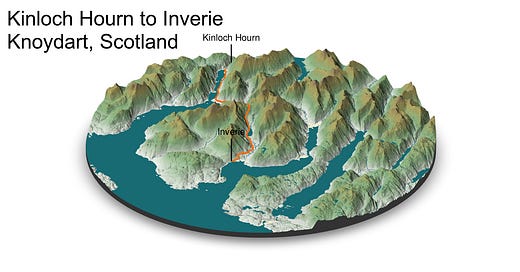

The full result is at the top of this post: a 360° panorama of the route from Kinloch Hourn to Inverie, based on Ordnance Survey data1.

A history of Knoydart: Scotland’s inaccessible peninsula

Knoydart is a peninsula on the west coast of Scotland. The Sound of Sleat separates it from the Isle of Skye. It is in an area called the Rough Bounds, so-called for the fact that even by the standards of the Scottish Highlands it is remote and inaccessible.

Bonnie Prince Charlie

Pictured on the map south of Knoydart is a village called Arisaig. It was from near there that Bonnie Prince Charlie fled Scotland after his failed attempt to restore the Stuart dynasty of his grandfather James VII of Scotland (and James II of England).

He landed in Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides from France with only seven men, called the Seven Men of Moidart. After a daring march on Edinburgh his newly-assembled army invaded England. They reached as far south as Derbyshire before turning back. The young prince’s army were then routed at the Battle of Culloden in April 1746.

The British government forces were in pursuit of the prince. He managed to disguise himself and spent the summer hiding himself among sympathetic villagers all around the western Highlands and Islands until he escaped to France that September. A reward of £30,000 (more than £5m in today’s money) was offered for his capture but no one turned him in.

In Our Island Story, H.E. Marshall tells the tale of one sympathiser in particular called Flora Macdonald. She gave the prince a dress to wear and a cover story that she was her maid2:

Disguised as Flora Macdonald’s maid, Prince Charlie travelled for many days, escaping dangers in a remarkable way. For the Prince made a very funny-looking woman. He took great strides, and managed his skirts so badly that, in spite of the danger, his friends could not help laughing. “They do call your Highness a Pretender.” said one. “All I can say is that you are the worst of your trade the world has ever seen.”

When there was no need for Flora to go further with the Prince, they took a sad farewell of each other [at Arisaig]. “I hope, madam,” said he, bending over her hand and kissing it, “we shall yet meet at St James’s.” By that he meant that he still hoped to be king some day, and welcome her in his palace of St James’s in London. Then he stepped into the boat which was waiting for him, and Flora sad sadly by the shore, watching it as it sailed farther and farther away.

There was to be no triumphant final act for Bonnie Prince Charlie. He became “a broken ruined man, and he lived a wanderer in many lands” before dying in Rome in 1788.

The Highland Clearances reach Knoydart

About 100 or so people live in Knoydart today3, mostly in the village of Inverie.

The population was not always so few. In his excellent book The Highland Clearances, Eric Richards tells the story of how the poor crofters of Knoydart, like so many others around the Highlands, were removed to make way for more profitable and less troublesome sheep.

Knoydart was part of a larger estate that belonged to Clan MacDonnell of Glengarry. The fifteenth of their name was a rather ostentatious and flamboyant character who died leaving the estate with large debts. His son Aeneas sold most of the lands off except Knoydart to try to balance the books. He tried to emigrate to Australia to improve his financial fortunes but returned to Inverie and died there in 1842.

In 1853 the administrators of the estate, including his mother Josephine, began the clearances of the 600 or so people who eked out a living on it. Probably mindful of how clearances in the Sutherland estate and other parts of Scotland had provoked outrage in the preceding decades, they offered the locals a free ticket to Canada or Australia and forgiveness of their rent arrears. Some 400 people accepted these terms but only 332 people arrived in Canada in September of that year.

A number of sick tenants and those who refused to move remained on Knoydart. This is where the story turns ugly (or uglier). The landlords continued to use legal action to force the tenants off their estate but they also resorted to burning down their shelters and pursuing them around the countryside as winter closed in.

The Scotsman’s correspondent reported at the time4:

On the third evening, when returning to Inverie, the factor’s party came upon a small boat house erected on the shore, at Doune, which they had overlooked. In this the ejected families had huddled at night, for two nights, not daring to put up any artificial shelter. Fire was immediately applied to the roof, and the structure burned down. This completed the work of destruction, and eleven families were left absolutely without shelter - for unfortunately for them the coast of Knoydart has no caves in which protection from at least the rain might be found.

Those few who remained passed the winter in abject poverty, as the Inverness Courier reported:

The place in which Kate [MacPhee, 54] lived was nine or ten feet long, five or six feet broad, and three feet in height. It was made up of branches of trees, brackens, and rags, and covered with a piece of canvas and an old Scotch blanket, fixed by cords and wooden pins. There was a sort of porch or entrance on the east side of the hovel, made of larchwood and divots. The door was barely sufficient to admit a full sized person, and then only by going on hands and feet and crawling in, which I had to do when I went in., As to the condition of the interior, a brood of young rates was found in Kate’s bed when she was removed. Such was the wretched place in which this poor woman took her abode and lived throughout the whole of the late tempestuous winter.

The estate was sufficiently emptied of its tenants to be sold off a few years later.

The route from Kinloch Hourn to Inverie

Back to the present day, the closest you can get to the Old Forge pub by car is a hamlet called Kinloch Hourn. As with many long treks, getting to the start line is in itself is no small feat. Daniel Stables of BBC Travel described it as ‘two hours of knuckle-whitening jags around hairpin bends and past sheer descents’ in a taxi from Fort William.

The first part of the trek follows the shore of Loch Hourn. Stables said it was ‘mostly rocky and easy to discern, but often collapsed into boggy marsh, which sucked our boots and smeared our ankles in mud.’

Having rounded the corner of the mountains alongside the loch, most walkers elect to spend the night at Barrisdale bothy.

Robin McKelvie of the Guardian described the next morning’s section:

The next morning is my toughest, but sore knees seem trivial as I turn my back on the brightening waters of the loch to forge up through mist-shrouded mountains. I battle the wind tunnel of 450-metre Mam Barrisdale pass with a brace of golden eagles and then descend towards Loch Dubh.

His description checks out. If you examine the close-up below you can see how the steep incline of the Mam Barrisdale pass awaits as you climb out of the valley in the foreground.

Once you reach the top it’s downhill after that, skirting around the north side of Loch Dubh. To the north is the towering 1,025m peak of Ladhar Bheinn. This mountain, which I had never heard of until I start writing this post, is taller than any peak in England. This was something I realised when I drove the North Coast 500: the terrain in the Highlands is so much wilder than anywhere in England or even Wales. There are mountains there that hardly seem to have names which reach higher into the sky than almost anything you will find further south.

This is the sight of the Old Forge that awaits you as you arrive in Inverie.

The enduring importance of land ownership in the Highlands

There are vast amounts of land in places like Knoydart but it’s obvious from its history that who owns it and how it’s used is hugely important.

There is a memorial at Inverie to the so-called Seven Men of Knoydart. Echoing the name given to the men who followed Bonnie Prince Charlie two centuries earlier, these seven men tried to stage a land raid on Lord Brocket, a Nazi sympathiser and owner of the land at the time. As Josephine MacDonnell did a hundred years earlier, he successfully employed the law against the men before selling the estate some time later.

It was in this historical context then that the Old Forge pub in Inverie was the subject of the community buy out.

The Guardian reported last year:

“It’s a bit of a cliche, but when you live in such a small community the pub plays a much bigger role than just somewhere to eat and drink,” says Stephanie Harris, secretary of the Old Forge Community Benefit Society, which now owns the pub.

“In the past it was where everything happened: birthdays, weddings, when a new baby came home from hospital that was the first place they visited. It was the place where everyone came together.

The pub is closed for refurbishment at the time of writing and is set to reopen in April. When it reopens it will seek to become once again the place where everything happens.

If you can’t make the trek from Kinloch Hourn to Inverie you can always get the ferry from Mallaig instead. But if you can walk it I’m sure the pint at the end of tastes that much sweeter.

Full citation: Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2023, licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. Google My Map data from The Guardian, A two-day Highlands walk to Britain’s most remote pub: the Old Forge, Knoydart, retrieved February 2023

H.E. Marshall: Our Island Story (2005)

The Rough Guide to the Scottish Highlands & Islands (2017)

Eric Richards: The Highland Clearances (2016)

Share this post